Native Nuclear

A new organization named Native Nuclear is empowering Native communities, uplifting tribal sovereignty and traditional indigenous values through energy, education and dialog.

The entire edifice of modern society is built upon energy. Energy is not just an important industry, it is the industry which enables all other industries. While nuclear energy may not be the only arrow in the energy quiver, nuclear is going to be an extremely important component of the future U.S. energy portfolio. Many of the resources necessary for a successful renaissance in nuclear energy, such as uranium and thorium, are abundant on Native lands.

Native Americans’ involvement with the nuclear industry began in the 1940s. At that time, uranium mining companies were given extensive latitude by the Federal government to operate on tribal lands in an existential race to develop a nuclear weapon before Nazi Germany, an effort which would ultimately end World War II in Japan. As a result, tribal relations with the uranium mining companies quickly became strained and abusive. Many Native Americans rightfully remain skeptical of the nuclear energy industry, associating it with past injustices.

Scott Lathrop of the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Tribe believes it is crucial for Native Americans to re-evaluate their position on the nuclear energy industry for the benefit of future generations. Despite the chequered past of the nuclear industry, Lathrop emphasizes the current importance for Native Americans to look beyond the past and learn about the potential benefits of nuclear energy.

Lathrop has recently founded Native Nuclear, a nonprofit organization dedicated to educating and engaging Native communities and promoting the incorporation of Native American perspectives and leadership in sustainable energy solutions, particularly in the nuclear energy sector.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

At the end of World War II, and thereafter during the Cold War, the U.S. government systematically performed atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons as a matter of perceived national survival. Accordingly, the U.S. frantically searched for domestic supplies of uranium, initially to support deployment of nuclear weapons and eventually to power the peaceful civilian development of nuclear energy to generate electricity. In the pursuit of national security and the rush to develop civilian nuclear power, the Atomic Energy Commission and uranium mining companies often failed to pursue the safety and environmental precautions which would now be considered imperative.

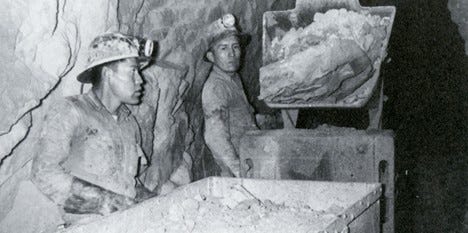

Uranium Mining

Perhaps the most egregious historical injustices have inured from the mining of uranium on tribal lands. From the 1940s to the 1980s, the U.S. government and private companies extracted uranium from Native lands. Many Native tribes were affected, including, but not limited to, the Hopi, Zuni, Havasupai, Laguna Pueblo, Acoma Pueblo, Oglala Lakota, Ute, Southern Ute, Apache, Hualapai, Tohono O’odham, Spokane, Lakota, Arapaho and Crow. Almost certainly, the most impacted tribe was the Navajo Nation, which served as the largest supplier of uranium used for nuclear weapons during the Cold War.

Native American workers were often employed in dangerous conditions without appropriate protections or knowledge of the health risks. Thousands of uranium mines were abandoned, left to contaminate soil, water, and air. High rates of cancer, kidney disease, birth defects and neurological disorders among Native communities are attributable to the mining and processing of uranium. Many water sources on Native lands remain contaminated and cleanup has been slow and underfunded.

Nuclear Testing “Downwinders”

From 1945 to 1962, the U.S. conducted approximately 215 atmospheric nuclear tests, mostly at the Nevada Nuclear Test Site. Radioactive contamination (“nuclear fallout”) travelled downwind from the test sites and spread across vast swaths of the western United States. Native communities in Nevada, Utah and Arizona were disproportionately impacted by radioactive fallout.

“Downwinders” (people living down-wind of nuclear tests) were exposed through inhalation of radioactive particles, consumption of contaminated food and direct contact with radioactive fallout. Exposure to radioactive fallout from the atmospheric testing has been linked to elevated rates of certain cancers and other health problems. Many Native communities still have not been not adequately compensated for the damage and suffering resulting from more than a decade of atmospheric nuclear testing.

Targeting Tribal Lands for Waste Storage

The U. S. Department of Energy also made plans to construct a permanent geological repository for spent nuclear fuel at Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Indeed, the Federal Government spent approximately $13.5 billion constructing a permanent deep geological waste repository at Yucca Mountain. However, the Yucca Mountain repository is located on Western Shoshone land protected by the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley. The Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository was conceived on sound geologic and scientific principles. However, the project should not move forward without unequivocal consent from the Western Shoshone Tribe. Continued development of the Yucca Mountain site ceased in 2011 due to public and Tribal opposition.

For the reasons stated above, it is easy to understand why many Native Americans remain skeptical of nuclear energy and the industries that support it. Gracefully, we now live in a more enlightened era where tribal sovereignty and Native American rights are ascending. Large infrastructure projects now require a social license to operate, which should make us optimistic that consent-based siting decisions are becoming the norm.

A Journey to Energy & Nuclear Advocacy

Scott Lathrop, founder of Native Nuclear understands that society needs safe, reliable, abundant and affordable energy. Lathrop states that “…the pathway to affordable and reliable clean energy must include more nuclear energy.”

Lathrop is a member of the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Tribe in central California which has been Anglicized as Northern Chumash Tribe (hereinafter “ytt Tribe”). ytt Tribe has called the area near San Luis Obispo its home for over 12,000 years. About 1770, Spanish colonists began to settle along California’s central coast. Eventually, the Spanish dispossessed ytt Tribe of its tribal lands without consent or compensation. Many ytt Tribal members still live in the San Luis Obispo area. Lathrop grew-up in San Luis Obispo aware of his Native ytt Tribal heritage. Lathrop’s journey into nuclear advocacy has been derived from a lifetime of experiences and enlightenment.

When it was announced that the Diablo Canyon [Nuclear] Power Plant (hereafter “DCPP”) would be constructed in 1963, ytt Tribe was not consulted, despite the plant being constructed on the historical homeland of the Tribe. When Lathrop was a young County building inspector, he would routinely be required to inspect the construction at DCPP. Lathrop was vaguely aware that some people and organizations were opposed to nuclear energy in general and DCPP in particular. However, Lathrop never harbored any personal feelings of opposition towards nuclear energy.

Diablo Canyon [Nuclear] Power Plant Photo by Lionel Hahn, Reuters

Later in life, Lathrop began to recognize that nuclear was not only a great source of energy, but it was in alignment with his Native values of mother earth, father sky, and life water (blood). Lathrop discovered that wind and solar energy require vast natural resources and require large amounts of land. However, using energy dense fuels to generate nuclear energy requires the exploitation of far fewer natural resources and less land. In fact, nuclear energy used to make electricity utilizes approximately 1/16th of the amount of natural resources required by solar and 1/10th of the amount of natural resources required by wind to generate an equivalent amount of electricity.

The Apparent Demise of Diablo Canyon Power Plant

In 2016, Pacific Gas & Electric announced that it planned to shut down DCPP. The Diablo Canyon Decommissioning Engagement Panel was formed to assist in the orderly decommissioning of the plant and restoration of the plant site. Pursuant to California law, the Decommissioning Panel was required to consult with legitimate Indigenous people of the San Luis Obispo area regarding the decommissioning and reclamation of the Diablo Canyon Lands. Lathrop was appointed to serve on the Panel by his Tribe.

At the time that PG&E decided to shut down DCPP, the plant provided about 9% of California’s total electricity and almost 25% of its “low-carbon” electricity. Lathrop soon realized that shutting down DCPP in a state which aspired to ambitious CO2 reductions, was sheer folly. However, saving DCPP was not Lathrop’s fight. In fact, Lathrop soon surmised that shutting down DCPP might potentially provide ytt Tribe an opportunity to recover a small portion of its ancestral homelands.

When PG&E originally decided to construct DCPP, the California utility acquired approximately 12,000 acres of land upon which to construct the power plant. However, the actual plant site only comprises only a paltry 750 acres of land. Therefore, the remainder of the Diablo Canyon Lands remain mostly undeveloped. PG&E made it known that they did not desire to retain ownership of the 12,000 acres once DCPP was closed. Lathrop helped lead an effort by ytt Tribe to purchase PG&E’s Diablo Canyon Lands. It appeared that ytt Tribe, in partnership with Cal Poly and The Land Conservancy of San Luis Obispo County, had made a deal to jointly acquire the Diablo Canyon Lands.

However, California’s urgent need for electricity coupled with dynamic political events, seemingly conspired to derail ytt Tribe’s “Land Back” efforts. In 2019, California began to suffer brownouts and blackouts of electricity. Simultaneously, groups like Mothers for Nuclear and Standup for Nuclear were aggressively advocating to keep DCPP open. These advocacy efforts together with the emerging realization that DCPP was needed to provide clean, reliable electricity, ultimately culminated in a decision by California lawmakers to allow DCPP to remain open. Regrettably, the decision to keep DCPP open represented a setback for ytt Tribe’s efforts to recover a small part of its historical lands. Nevertheless, Lathrop and ytt Tribe continue to vigorously pursue a deal to gain ownership of all or a portion of the Diablo Canyon Lands.

Through his involvement with the Decommissioning Panel, Lathrop began to understand how utterly essential DCPP was to California and the San Luis Obispo community. Over time, Lathrop became an enthusiastic advocate for DCPP specifically and nuclear energy more generally. Lathrop also learned that one of the most common public concerns about nuclear energy is what to do with the so-called nuclear waste which might be more correctly called partially spent nuclear fuel.

Partially Spent Nuclear Fuel Dilemma

A typical U. S. nuclear power plant is powered with enriched uranium. Once the uranium fuel has been “used,” it is removed and stored in dry casks made of concrete, steel, lead and other materials. In reality, the amount of accumulated spent nuclear fuel in the U. S. is surprisingly small. All of the spent nuclear fuel produced from all U.S. commercial power plants over the past 70 years could fit into a single football stadium. The nuclear industry is the only industry which accounts for all of its waste throughout the full energy lifecycle.

The U. S. Department of Energy (“DOE”) is legally responsible for the disposal of the partially spent nuclear fuel produced in the U.S. For many years, the long-term plan has been to store the spent fuel on-site at each of the nuclear power plants until a permanent subterranean repository could be developed to store the “waste.” However, now that Yucca Mountain Project has been scuttled, the U.S. does not currently have a permanent repository for spent fuel.

However, a new strategy is emerging for managing partially spent nuclear fuel. Once a typical fuel rod has been removed from a U.S. nuclear power plant, only about 4% of the energy contained in the uranium has been used. It is possible and sometimes desirable to repeatedly reprocess certain types of partially spent nuclear fuel and re-use it over and over again until a significant portion of the energy is eventually harvested. In fact, that is exactly what countries like France have been doing for decades. France derives approximately 70% of its electricity from nuclear energy and reprocesses a significant portion of its partially spent fuel. Therefore, we should not necessarily look at partially spent nuclear fuel as some sort of unsolvable nuisance. Instead, we should view the U.S. stockpile of partially spent fuel as a potentially valuable asset to be nurtured and reused when possible.

Section 5c of the Executive Orders dated May 23rd, 2025 Deploying Advanced Nuclear Reactor Technologies for National Security instructs the Departments of Defense & Energy to "…..to site, approve, and authorize the design, construction, and operation of privately-funded nuclear fuel recycling, reprocessing, and reactor fuel fabrication technologies…." Therefore, it now appears that the U.S. may be on a path to reprocessing and recycling a significant portion its partially spent nuclear fuel, thereby providing fuel to help power an emerging fleet of new advanced nuclear reactors for decades or longer. However, reprocessing is complicated and it is imperative that the U.S. accelerate the development of reprocessing and enrichment facilities.

Once spent nuclear fuel has been repeatedly reprocessed, eventually, there will be a small residue of radioactive waste which will need to be stored in a permanent repository. Certain fuels which cannot be reprocessed will need a permanent waste repository. Therefore, the U.S. still needs to develop a permanent repository for radioactive waste; however, it is not as urgent as it once seemed.

In the meantime, DOE wants to continue storing partially spent nuclear fuel in the current manner. However, DOE now envisions consolidating the spent fuel storage sites from approximately 90 current locations to approximately 10-12 “interim” storage sites until a permanent deep geological repository can be developed.

DOE acknowledges the mistakes of the past and does not plan to select future storage sites for nuclear waste without the collaboration of the hosting community. To be sure, there will many communities that will not want to host an interim or a permanent repository for radioactive waste. Nevertheless, buoyed by better understanding of the safety factors and the economic incentives, there will almost certainly be many communities eager to develop storage sites for partially spent nuclear fuel.

As a result, DOE now wants to identify communities which might be willing to host “interim” storage facilities (for 50+ years). The interim waste storage sites might eventually also be located near nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities, which could provide additional economic development opportunities.

In order to inform the public and identify potential communities willing to host interim storage sites, DOE has established the Collaboration-Based Siting Consortia (“CBSC”). The CBSC has provided grants to organizations willing to meet with local communities to discuss the storage of spent nuclear fuel. Native Nuclear is a member of one such consortium. Together with North Carolina State University and Mothers for Nuclear, Native Nuclear is traversing the U.S. to discuss collaboration-based siting of spent nuclear fuel.

Native Nuclear – A pathway to a better future

Lathrop believes that a future where energy is abundant, reliable, affordable and produced in an environmentally responsible manner, is a future where nuclear energy must play a prominent role. Lathrop acknowledges the severe injustices borne by Native Americans in the past pursuit of nuclear weapons. Lathrop also appreciates the feelings of betrayal and lack of trust many Native Americans feel for non-Native institutions.

Nevertheless, Lathrop believes that nuclear energy is consistent with the values of most Native Americans. Lathrop states “When it comes to utilizing creator-given resources, we must limit the impacts on the environment by taking little, maximize the benefit, and returning limit waste into the environment. Nuclear power stands out for its small environmental impacts compared to other energy sources and should not be overlooked by Native Americans due to the fears of the past”.

Lathrop wants Native Americans to consider the profound benefits of nuclear energy to the world broadly and to the individual Tribes more specifically. Therefore, in order to help Native Americans pursue a sustainable future which includes nuclear energy, Lathrop decided to form Native Nuclear, a non-profit organization which is led by Native Americans for the benefit of Native Americans.

Native Nuclear strives to support Indigenous self-determination and amplify Native voices. Native Nuclear seeks to promote a do-it-yourself attitude and voice of optimism within the Native communities. Native Nuclear aspires to create pathways for Native voices to join the world of science and energy. Native Nuclear endeavors to foster respectful, long-term relationships between tribal entities and non-tribal entities. Ultimately Native Nuclear seeks to open doors to allow indigenous peoples to lead in the nuclear energy sector. Native Nuclear hopes to serve as an intermediary between nuclear energy professionals and Native tribes.

“We are uplifting Native voices in an industry that has systematically silenced them for decades”

Samantha Brandts, Native Nuclear

Native involvement and participation in nuclear energy could manifest (i) the construction of new advanced nuclear power plants on Native lands; (ii) the mining and processing of uranium and thorium on Native lands; and (iii) the development interim storage sites for spent nuclear fuel and the reprocessing of such partially spent nuclear fuel on Native lands.

In addition to its participation in the Collaboration-Based Siting Consortia, Native Nuclear has embarked on a proactive effort to engage with Native Tribes across the nation to share ideas about energy development. Native Nuclear is also developing educational programming about nuclear energy and offering scholarships to Native Americans who seek to study energy and nuclear related subjects at university.

Despite Native Nuclear’s passion for nuclear energy, the organization insists that Native sovereignty must always be honored by non-Tribal entities including the Federal Government. Accordingly, nuclear related activities such as mining, uranium processing, spent fuel storage, and nuclear construction, should be never be forced on any Tribal community without their consent. Native Americans should be afforded an equal opportunity to participate in the coming renaissance in nuclear energy!

ytt Tribal member Scott Lathrop standing on the land upon which the historical village site of tsɨtʸɨwɨ is located on Diablo Canyon Lands.

Learn more about Native Nuclear at www.nativenuclear.org

Learn more about collaboration-based siting at Consent-Based Siting Consortia | Department of Energy

Thanks to the following people who helped make this article the best it could be:

Scott Lathrop, Native Nuclear

Samantha Brandts, Native Nuclear

Ryan Pickering, Native Nuclear

Heather Hoff, Mothers for Nuclear

Fereshteh Bunk, Mothers for Nuclear

Tamara Haynes-Norton, Fire2Fission

Brooke Morrison, Solestiss

Thanks for your support! I liked Atomic Dreams so much that I have given away 18 copies of the book!

Thank you, Doug! This was great!

Learn more about Native Nuclear on our new website at https://www.nativenuclear.org/. :)