PG&E’s Amelioration for ytt Northern Chumash Tribe - Part 1

Pacific Gas & Electric, California and Gavin Newsom have a historic opportunity to facilitate the return of a meaningful amount of land to the Indigenous people of California’s Central Coast

Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) and the State of California have a rare opportunity to do something historic and consequential for the people Indigenous of Central California’s Pecho Coast. PG&E had indicated a willingness to consider a private sale of approximately 12,000 acres of land in and around the Diablo Canyon [Nuclear] Power Plant (herein called “DCPP”) to the local Native American tribe, upon whose historical homeland DCPP is constructed. This opportunity would concurrently benefit yak tityutityu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe (herein called “ytt Tribe”), PG&E’s ratepayers and stockholders, without accruing any cost to the taxpayers of California.

PG&E has suffered two bankruptcies during the past 25 years and continues to feel the financial burden of wildfire-related lawsuits. This proposed transaction to sell the Diablo Canyon lands to the local Indigenous ytt Tribe would provide a needed infusion of cash into PG&E’s coffers, while simultaneously facilitating ytt Tribe to regain a very small portion of the native lands taken from them without agreement or compensation approximately 250 years ago. However, California has passed legislation which has stymied ytt Tribe’s efforts to regain a small portion of its ancestral homelands. According to Scott Lathrop, CEO of ytt Northern Chumash Non-Profit, “With the recent passage of California Senate Bill 846, the State of California has impeded a private land sale transaction between PG&E and the ytt Tribe, which amounts to the continued colonization of these Native American lands.”

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

yak tityutityu yak tiłhini Tribe (Hispanicized as Obispeño and subsequently Anglicized as Northern Chumash) are the Indigenous descendants of the San Luis Obispo area in Central Coastal California. Current tribal membership comprises families who have documented ancestral lineage and whose history has been centered in this region for at least 12,000 years. The tiłhini were skilled artists and craftspeople, particularly in basketry and tool-making with their exquisite engineering and fabrication skills. They were also skilled in shell bead production, often made from Olivella shells with intricate designs. These beads were part of an extensive trade network connecting tribes throughout Central and Southern California. The tiłhini also maintained their cultural heritage by singing traditional songs and crafting musical instruments. The tiłhini had a governance system based on kinship and were adept land stewards and managers, engaging in what is now recognized as skilled land management.

Their language, known as tiłhini, is a member of the Chumashan language family and is documented with the Language Identifier “obi 639-3.” Unique to tiłhini is the absence of capital letters in its linguistic structure, reflecting its distinct cultural and linguistic roots. Immediately prior to the arrival of Europeans, the tiłhini ytt Tribe lived in several principal villages along the coast and inland areas of what is now San Luis Obispo County. These villages which relied on abundant marine and terrestrial resources on the coast include the village of tsɨtʸɨwɨ among many others (Hispanicized today as the “Pecho Coast”). Pecho is the Spanish word for chest and tsɨtʸɨwɨ is the tiłhini word for breast or chest. In 2018, collaborative work in identifying the village of tsɨtʸɨwɨ with ytt Tribe, PG&E, California Polytechnic State University (“Cal Poly”), were recognized with the Governor’s Historic Preservation Award.

Source: Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, January 2006

In 1542, Portuguese explorer João Rodrigues Cabrillo and his crew, sailing under the Spanish flag, are believed to have been the first Europeans to make contact with hunter-gatherer tribes in “Alta California.” Cabrillo’s surviving diary documents the names and estimated population counts of many native villages across Central and Southern California.

European contact with Central Californian Indigenous peoples was minimal for over two centuries following Cabrillo’s expedition. Around 1769, Spanish soldiers and Franciscan missionaries began arriving to colonize and Christianize the Indigenous peoples, establishing military presidios and Catholic missions throughout Southern, Central and parts of Northern Coastal California. In 1772, Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa was established in the heart of the tiłhini ytt Tribal area, in the city currently known as San Luis Obispo, California.

The establishment of the Spanish missions marked a tragic turning point for the tiłhini people, as missions introduced foreign diseases and catastrophically disrupted much of their traditional ways of life. The tiłhini population was devastated by outbreaks of smallpox and measles, introduced by the Spanish. These diseases ravaged tiłhini communities, leaving ytt Tribe fragmented and vulnerable. Faced with starvation and the loss of their traditional lands, some tiłhini moved to the mission communities seeking stability and protection.

The Spanish governed the occupied tiłhini territories with ruthless efficiency. Many tiłhini Chumash people were forcibly moved by the Spanish from their native villages into Franciscan missions between 1772 and 1817 in order to facilitate their assimilation and spiritual conquest. The mission system was not always benevolent and served in aiding the process of colonization. Many tiłhini people became forced laborers for cleaning, cooking, agricultural work, tending animals, digging irrigation ditches and constructing the mission and other structures. The rape of women and girls was not uncommon. Moving from villages into the missions brought the tiłhini people into close quarters with each other and relocated Indigenous groups from other homelands, where they were exposed to outbreaks of influenza, tuberculosis, typhus, syphilis, and dysentery. The unsanitary conditions and overcrowding in the missions further reduced the tiłhini population, eroding their cultural and physical autonomy.

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa

Eventually, Mexico declared independence from Spain and the tiłhini territory was ceded to Mexico in 1834. The Mexican government subsequently secularized the missions, redistributing mission lands (previously taken from the tiłhini Chumash) to private Mexican landowners. This privatization of lands further dispossessed the tiłhini people of their ancestral territories, leaving them without access to traditional resources. Many of the tiłhini that were driven off of their native lands were conscripted by their Mexican overlords.

In 1846, the California Republic declared independence from Mexico; however, the tiłhini Chumash territory remained firmly under the control of Mexico until February 2nd, 1848, when the United States defeated Mexico in the Mexican-American War. At the termination of the war, California became a U. S. Territory, until it gained Statehood in 1850 as the 31st State of the United States of America.

Tragically, the affairs of the tiłhini Chumash did not improve under the stewardship of California and the United States. Ranchers, miners and other commercial enterprises continued the pattern of occupation and exploitation of the tiłhini Northern Chumash people and their lands. During the ensuing century, bands of Indigenous tiłhini Northern Chumash continued to be disbursed and disenfranchised without land of their own.

“That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected.”

Peter Hardeman Burnett, Governor of California, January 6, 1851

Through the forces of colonization, the tiłhini Chumash tribal communities lost all of their land. Only the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Mission Indians (Ynezeno Chumash) have been able to re-acquire a small tribal reservation. In 1901, the Santa Ynez Chumash Tribe was granted a tiny tribal reservation (127 acres), which was expanded to 1390 acres in 2019. However, the other seven Chumash Tribes have never had any of their native lands returned to them. ytt Tribe, native to the San Luis Obispo area, has never enjoyed a tribal reservation of its own.

THE RISE OF THE ATOMIC AGE & THE VISION FOR DIABLO CANYON

Nuclear energy has enjoyed a prominent and distinguished history in California. Following the conclusion of World War II and the dawn of the atomic age, there had been plans to construct ten or more nuclear power plants in California. The Valecitos Boiling Water [Nuclear] Reactor constructed in Alameda County, California was mainly used for testing new technologies. Nevertheless, in 1957, Valecitos became the first privately owned nuclear power plant in the United States to deliver electricity to a public utility grid. The Valecitos commercial reactor only operated until 1963. In 1960, PG&E began construction of the Humbolt Bay Nuclear Power Plant near Eureka, California. The plant was commissioned in 1963, making it one of the earliest commercial nuclear power plants constructed in the United States. The plant was shut down in 1976 due to concerns about the plant’s perceived inability to withstand significant seismic events.

In 1964, Southern California Edison began construction of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station on the Pacific Coast near San Clemente, in Southern California. Units 1, 2 and 3 were commissioned in 1968, 1983 and 1984 respectively. In 1966, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District began planning to construct a nuclear power plant near the State’s capital. The Rancho Seco Nuclear Generating Station, located approximately 30 miles southeast of Sacramento, was commissioned in 1975; however, operational failures and economic considerations caused the plant to be permanently closed in 1989, making it the only nuclear power plant in the U. S. to be shut down as a result of a public referendum.

In 1963, PG&E announced plans to construct five nuclear reactors near the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes in Central California. However, almost immediately, protests erupted over concerns that the proposed location of the nuclear facility would be detrimental to wildlife habitat. The Sierra Club and other environmental organizations successfully convinced PG&E to move the proposed nuclear power plant to the Central California coast near San Luis Obispo, to be situated on the tribal homelands of ytt Tribe. ytt Northern Chumash families were not part of the important discussion about locating the nuclear power plant on their native lands. According to tribal leadership, ytt Tribe learned about the decision at same time as the remainder of the public. At that time, the facility was named Diablo Canyon Power Plant.

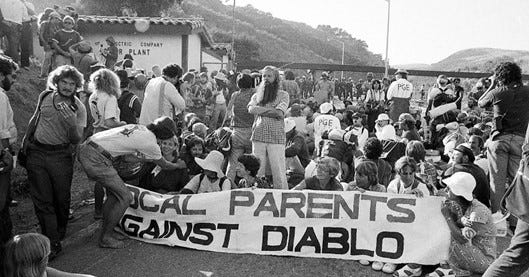

Once the decision had been made to construct DCPP near San Luis Obispo, PG&E (by and through various corporate affiliates) acquired approximately 12,000 acres of land along the Pecho Coast, all of which are ancestral lands of ytt Tribe. The land was acquired from private ranchers and landowners and construction began on DCPP on April 23, 1968. However, before construction even commenced, many organizations and individuals protested the construction of DCPP. Some protested the site selected for DCPP, others voiced opposition specifically because of safety concerns, and still others objected simply because they opposed nuclear energy in principle.

At its inception, the Sierra Club had supported nuclear energy because of its small footprint and the clean energy it provided. However, in 1967, a year before construction started at DCPP, some members of the Sierra Club began to change their views and oppose nuclear energy. Certain members of the Sierra Club believed that nuclear energy would create too much cheap electricity and speculated that humans would be too socially immature to manage the immense prosperity created by abundant and affordable nuclear energy. Eventually, the Sierra Club went full “Benedict Arnold” and commenced a campaign of opposition to DCPP.

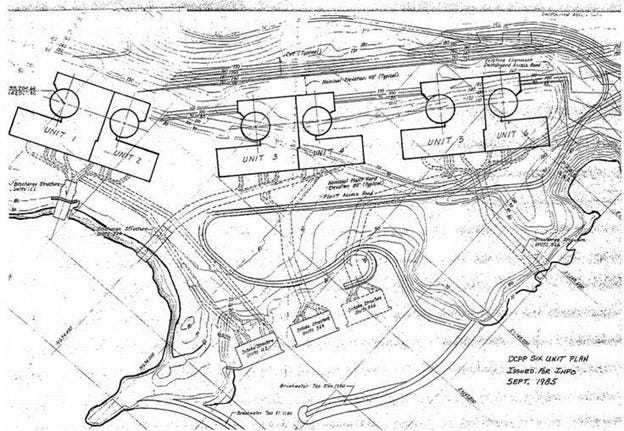

In the wake of the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, opposition to DCPP further intensified. As a result of changing public sentiment and emerging legal actions in opposition to DCPP, the completion of Units 1 & 2 was delayed significantly. In the aftermath of the Three Mile Island accident, PG&E decided not to construct Diablo Canyon Units 3, 4, 5 and 6. Following 14 years of hearings, protests, blockades, interventions, court cases, retrofits and reconstruction, Diablo Canyon Unit 1 was finally commissioned in 1985 (Unit 2 was commissioned in 1987).

Depiction of plans for the original six reactors at Diablo Canyon [Nuclear] Power Plant.

THE APPARENT DEMISE OF THE DIABLO CANYON [NUCLEAR] POWER PLANT SIGNALED THE EMERGENCE OF A POTENTIAL “LAND BACK” OPPORTUNITY FOR TItHINI NORTHERN CHUMASH

Although the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station and DCPP were both eventually completed and produced clean, reliable, affordable electricity, the controversy over nuclear energy failed to subside. Over time, more and more Californians emerged in opposition to nuclear energy. Due in part, to pressure from environmental groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and Friends of the Earth, Southern California Edison decided to close San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in 2013 (at that time, SONGS was the only remaining nuclear power plant other than DCPP operating in California).

Prior to 2016, PG&E had been attempting to renew DCPP’s operating license. However, relentless opposition to nuclear energy in California forced PG&E to acquiesce to political pressure and in 2016, PG&E announced plans to shut down DCPP at the end of its approved operating license in 2025. Within weeks following this announcement, Mona Olivas Tucker, Chair of ytt Tribe, contacted PG&E to express the Tribe’s concern for the future of the Diablo Canyon lands.

ytt Tribe viewed the announced closure of DCPP as a possible opportunity to regain a modicum of the Tribe’s ancestral lands. In February, 2018 the Diablo Canyon Decommissioning Engagement Panel was formed to engage the local community regarding the impacts of decommissioning the plant and restoring the lands adjoining the plant. Under California law, it was imperative for the Diablo Canyon Decommissioning Engagement Panel to consult with legitimate Indigenous people of the San Luis Obispo area regarding the decommissioning and reclamation of the Diablo Canyon lands. Appropriately, PG&E began to consult with the local ytt Tribe regarding the reclamation of the land upon which DCPP is located.

On December 5, 2019, the California Public Utilities Commission (“CPUC”) finalized a Tribal Lands Transfer Policy that allows for the transfer of land from investor-owned utilities to Native American tribes with a historical interest in the land. When a utility begins the process of disposing of land, the policy creates an expectation that the utility negotiate a transfer to the tribe before putting the land on the market. This policy, furthers the CPUC's goals of recognizing and respecting native sovereignty, and of returning tribal lands to their rightful owners.

CPUC Tribal Lands Transfer Policy

PG&E made it known that once DCPP was shut down, they had no desire to retain the approximately 12,000-acre compound upon which the nuclear power plant is located. Slowly, a seemingly beautiful and mutually beneficial solution began to emerge. ytt Tribe partnered with the Land Conservancy of San Luis Obispo County (“SLO Land Conservancy”) and California Polytechnic State University (“Cal Poly”), therein collectively called “ytt Tribe Conservation MOU” to prepare the Joint Land Acquisition Proposal to Acquire and Protect the Pecho Coast Lands (“Joint Land Acquisition Proposal”).

In June 2021, the Joint Land Acquisition Proposal was submitted to PG&E. This critical legacy document proposed that after DCPP was decommissioned, ytt Tribe would purchase the DCPP site and the adjoining approximately 12,000 acres, thereby restoring a small, but salient, portion of the ancestral homeland to ytt Northern Chumash after 250+ years. The proposed transaction would also facilitate the creation of a conservation easement covering most of the 12,000 acres, to be administered by the SLO Land Conservancy and would also enhance Cal Poly’s educational mission to the State of California. The Vision Statement prepared by the Diablo Canyon Decommissioning Engagement Panel stated “The request for land ownership by the local Native American community should be acknowledged and considered as a valid claim for historical reasons…” There were lofty hopes that the ytt Tribe Conservation MOU could become a model for the state and perhaps the country, creating partnership with a local Indigenous Tribe, a local land conservancy, and a local State agency.

PG&E responded favorably to the Joint Land Acquisition Proposal and formal discussions proceeded with ytt Tribe Conservation MOU. Under the terms of the Joint Land Acquisition Proposal, PG&E would not gift the land to ytt Tribe (which many believe would actually be in alignment with historical justice), but rather the Tribe would purchase the land from PG&E. Simultaneously, ytt Tribe would finally have an opportunity to reclaim a small portion (18.75 square miles) of their native lands (originally the ytt Northern Chumash lands covered approximately 7,000 square miles). This transaction would not only benefit the Tribe, but it would also benefit PG&E stockholders and rate payers. ytt Tribe certainly did not have the financial resources to purchase PG&E’s Diablo Canyon lands. Fortunately, the commitment of the ytt Tribe Conservation MOU to pursuing a Tribal “Land Back” goal produced high interest from benefactors willing to donate money for the purchase of the 12,000 acres from PG&E. The terms of the Joint Land Acquisition Proposal envisioned a simple and seemingly perfect solution for all concerned parties.

The conclusion of this fascinating story (Part 2) will be published next week on Energy Ruminations.

Copyright 2024 Douglas C. Sandridge

Great Idea! Thanks for your support!

Thank you for this informative "back story" regarding the ytt Northern Chumash Tribe's ancestral lands and their connection to Diablo Canyon Power Plant (DCPP.) Californians for Green Nuclear Power encourages the ytt Northern Chumash Tribe to develop an agreement with PG&E for the tribe to receive a small payment for each megawatt-hour generated, akin to the "millage" that has been used to fund the DCPP decommissioning trust fund.